A rival nuclear power starting a shooting war in Europe just a few days earlier presents the kind of circumstance in which a State of the Union address could hypothetically be vital. But it is still likely destined to merely be bland news cycle chum. The chatterboxes on the cable channels and the pundits in the political press will debate the “expectations” for the speech, and we will all earnestly pretend to wonder whether our president — older now than Ronald Reagan was when he left office — will be able to summon some heretofore unobserved rhetorical genius to conciliate our sick and tired nation.

I hope that he will subvert expectations deliberately. Mr. Biden’s intrinsic political genius is his ability to act as a mourner and as a bearer of bad news. His greatest act of political bravery was to tell America, after 20 years of lies, that the war in Afghanistan was over and lost, and then to mostly keep quiet and stick to his guns. The stakes are much lower for a gaudy speech like the State of the Union, but he should really do the same. Go up the hill, deliver a dull litany of bullet points, get to bed early and consign this silly ritual to C-SPAN, where it belongs.

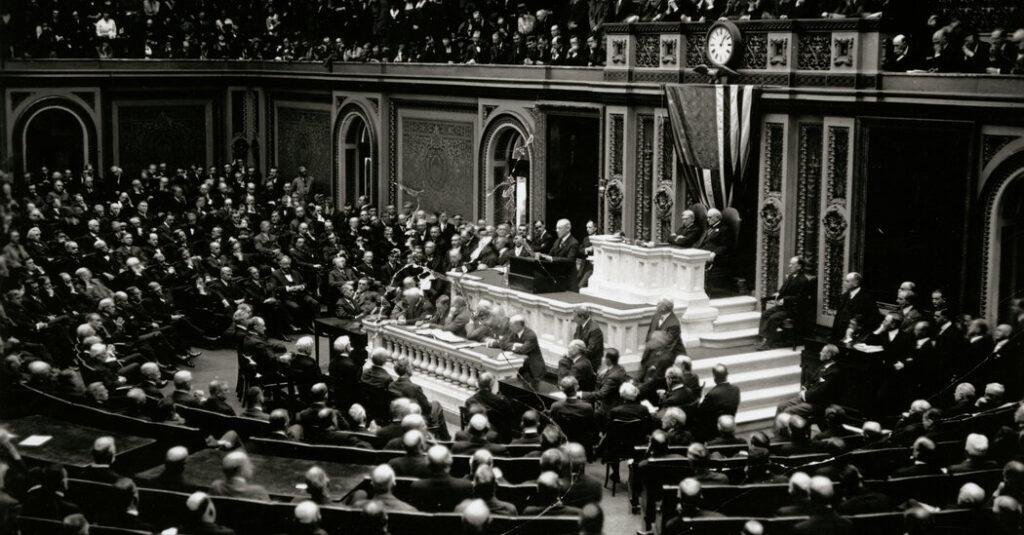

In 1796, writing to his great friend, Filippo Mazzei, an Italian physician, farmer, pamphleteer and gunrunner for the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson complained of the great changes in America since its independence. “In place of that noble love of liberty and republican government which carried us triumphantly thro’ the war, an Anglican, monarchical and aristocratical party has sprung up,” he wrote, lamenting the adoption of British “forms” of pomp and circumstance, especially by the executive and judicial branches. Mazzei’s enthusiasm overcame his discretion, and he promptly dispatched copies of Jefferson’s observations to friends around Europe. They were published in French and Italian, and then made their way back across the Atlantic to the United States, where they reputedly caused a personal rift with George Washington, whose regal presidency — complete with annual addresses to joint sessions of Congress, which Jefferson considered far too similar to a British monarch’s “speech from the throne” — was understood to be a target of Jefferson’s contempt.

Jefferson’s dream of a nation of independent yeoman farmers was a fantasy even in his own time (not to mention a bit hypocritical — can anyone imagine the squire of Monticello driving a horse and plow through 40 rocky acres of Appalachian Virginia?), but his hostility toward the monarchical trappings of an imperial presidency was not wrong. His dream would be undone as America became a continental empire, then a hemispheric power, then an overseas empire and a great industrial and military titan. The centrality and power of the presidency could only increase as America evolved into a modern, bureaucratic state. It was inevitable, with the advent of modern mass broadcast communications, that the president would become a figure of enormous cultural significance as well. By the 1930s, presidents were everywhere on the radio; by the 1960s and the gilded, media-centric presidency of John F. Kennedy, they were culturally ubiquitous, singular synecdoches for America itself.

We are too close to these people now. Pomp can stand a little silliness; it may even require it. But it can’t survive absurdity. The advent of social media ruined celebrity by imitating proximity, and the transformation of politicians into ruined celebrities further destroyed politics. To see an actor whom you only know from movies and glossy magazines glide down a red carpet once or twice a year in a wild dress and borrowed jewels is to be astonished; to live with her everyday eructations of bad musical opinions and worse food photographs is to be annoyed. Likewise in politics. Our ostensible leaders are social media addicts like the rest of us, only more so. Their court rituals and pagan traditions have lost all of their high masonic mystery. We find ourselves watching a regional industry dinner, the sorry spectacle of insiders wallowing in self-congratulation over rubber chicken amid too much applause.